The text is about me. It’s more of an analysis of myself and a conversation with myself.

Photo by Samuel Austin on Unsplash

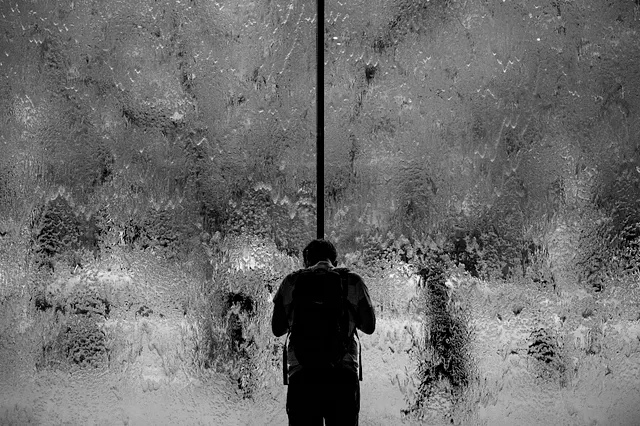

Throughout my life, the feeling I’ve had has always been the same: on the outside, normal and adaptive; on the inside, a few steps removed from the flow of the world. I could never mentally sync with people’s emotional rhythm, social expectations, or societal norms. I acted as if I did. With every passing year, this behaviour turned into a heavier burden.

I used to frame this as a personality difference, thinking “that’s just my character.” But the more I read about psychology, the more online tests I took, the more I realized it wasn’t that simple. As I read, I started finding myself in many of the concepts.

Neuroscience and psychology literature show that the way individuals perceive the world is shaped not only by personality differences but also by cognitive differences. No matter how much society pressures us to be the same, neural variability is what actually makes us different.

Of course, the more I read, the more confused I get. I’m not a psychologist, and I’m not defending the accuracy or consistency of online tests, but seeing the same patterns repeat over and over inevitably makes you think. It can’t be a coincidence.

Some sources say certain things would have been noticed in childhood, but there’s also the fact that the body’s adaptation mechanisms can suppress these neural differences. Children can copy different social behaviours, suppress themselves, hang back by overanalyzing, or appear “well-adjusted.” Outwardly, this can show up as things like pulling at hair, shaking arms and legs, seeming indifferent, feeling constant stress, social fatigue, escaping social environments, hating small talk, being known as calm, rational, humble—general “symptoms” that can be related to many things.

When I look back and reflect on myself, I realized there were actually a lot of clues. I was a misfitting kid on the inside but a well-adjusted one on the outside. As a quiet and compliant child, I managed to suppress many of these things and somehow cope with these differences. The reason I’m thinking about all this now is that this burden has grown; maybe I finally had the opportunity to feel like myself.

I don’t think I’m stupid or that I had a learning disability, but for as long as I can remember, I’ve never been able to understand lessons just by listening. I’d lose interest after 3–5 minutes. That’s why history, geography, and literature classes were always boring and mostly incomprehensible to me. What I did learn, I mostly learned by hearing and reading. I also remember sometimes making extra effort and fitting things into formulas in my head.

I’ve always been sensitive to touch. I never liked being touched or physical contact. It’s been like that as long as I can remember. I was emotionally neutral about many things and I liked being alone. I remember some moments from kindergarten: I would sneak into another room just to be alone, pretend to be asleep. It wasn’t that I didn’t enjoy spending time with friends. I did. But I also needed solitude. Throughout my school life and work life, I would often escape to the bathroom just to be alone for a bit and breathe, and stay there for quite a while. Sometimes just to be able to think.

I also remember some moments where there was a crisis and everyone was panicking, and I had this unnecessary calmness. Abstract thinking and quickly understanding conceptual systems have generally been an advantage for me. Understanding the concept was fast, but to go deeper, I needed focus. If a topic didn’t interest me, I’d struggle to concentrate and maintain that focus. With topics that did interest me, if I was convinced that I truly understood something, I didn’t want to waste time repeating it through practice. For example, when I was studying for the university entrance exam, in physics, maths, and geometry tests, I’d look at the question. If I was sure I could solve it, I’d just flip to the answer page. I wouldn’t bother solving it. As a result, I didn’t get any wrong in those areas in the actual exam. In areas where I practiced more and didn’t look at the answers, I had plenty of mistakes. I’m still like that. If I’ve understood something and I know how to solve it, I prefer not to waste time and just leave it to ChatGPT or Google. Especially in work life, it saves time.

All these traits are products of a complex neurocognitive structure. And again, contrary to what our entire education system and teachings imply, there’s no single “right.” There’s no single mental process either.

In trendy terms, I could say my autistic spectrum is high, I have attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, and emotional blindness. But then again, who doesn’t, right?

I wouldn’t actually say such a thing because I’m not an expert. And what I experience is not at a level I’d call an illness anyway. Then again, the definition of illness in psychology is a bit strange. A soldier who doesn’t want to fight is considered sick, for example. Or someone who doesn’t want to spend the majority of their life working.

So does this distractibility, indifference, lack of empathy, and self-centeredness affect my life? Absolutely. Still, it’s easiest to dodge it all by saying “this would’ve been caught in childhood.” And yet, there are things I’m trying to explain to myself.

Silent Separation from Childhood

When I think back, as I mentioned above, I realize I used to avoid social groups. I did experience things as a child too, but they were never extreme.

It’s been like this for as long as I can remember. I wasn’t a child who was excluded; I always had friends. But I always remember this feeling of watching things from the outside. It’s still like that today.

For example, I never understood “team spirit.” Being a few people together never equaled being a good team for me. I was never good at team sports either. Herd mentality has always felt foreign to me.

I can’t say I don’t like people, but my close friends say “you hate people.” I like loneliness in crowds, but big groups always exhaust me.

Similarly, I’ve never put down roots in cities. Moving always feels easy; settling down feels hard. When a place starts to feel “settled,” when I fill it with objects, I feel suffocated. For instance, lately I’ve been wanting to sell all my stuff. The only thing holding me back is logic.

I don’t feel attached to my past either. I realized this more when talking to friends. I have memories, things I remember, but I’ve never wished any of them would come back again, that I could relive those days. I don’t feel longing. If I think “those were good times,” it’s more of a rational statement than an emotional one. I also don’t fully remember many of my memories. They come to mind here and there, but they feel so distant that I can’t even explain it.

I remember we once had a reunion with my primary school friends. We did similar meetings once with my high school and university groups too. I only did each of these once. They were all the same. I couldn’t find anything to talk about, nor did I feel any nostalgic bond. I was mostly just observing from the outside, analyzing the situation. I could see how far the stories drifted from reality. I’d nod along meaninglessly to signal agreement. There were moments when I felt completely neutral in these gatherings. Or I’d only feel something when we discovered new common ground about the present rather than the past. Maybe that’s why I’ve become somewhat famous for being “disloyal” to my past.

There are many concepts in literature that could explain this. I don’t know if just calling it “lack of emotion” is enough or if it has a more sophisticated term. All I know is that I experience this in my daily relationships too. Of course, even “lack of emotion” is misunderstood. It depends on the situation. There are definitely no exuberant feelings. The sense of closeness and attachment is limited.

2. Loneliness and the Need for People

I’ve never had a problem with loneliness. The pandemic period was the best time for me. But I can’t cut people out completely either. There is a social need after all. My friends who define me usually say I’m reliable, sincere, natural, but someone who sometimes creates distance and is “unreachable.”

I generally avoid groups of 5–10 people. I enjoy deep communication with one person much more. When I think of my best friendships, they’re usually low-contact but high-trust relationships where even if we don’t see each other for months, the bond stays the same, and I know they’re there and they know I’m here. And I can’t say I really “have” a sense of time. When I see someone I haven’t seen in three years, it feels as if we saw each other an hour ago. I never feel the excitement of “after so many years!” Feeling close is an almost indescribable bond for me. That bond doesn’t break easily. But I also don’t have a constant need to talk, meet, or hear from people. My ex-girlfriends described my closeness as “on/off,” like a switch. I see it more as an open signal. Like it’s always on.

Some people explain this as an introverted personality, others as emotional blindness or something on the autism spectrum. Others just say, “you’re a complete narcissistic bastard.”

3. Sensory Sensitivity and Emotional Neutrality

Physical contact has always been hard. Crowds, sudden touch, hugging, physical closeness—they all make me uncomfortable. In my relationships, I solve this logically, but of course there are people who find me “mechanical” because of it.

Apparently this is called tactile defensiveness—a type of sensory processing difference (Dunn, 1997).

There was a time we were in a traffic accident. When I got out of the car, I had this strange feeling. A sense of neutrality toward the event. When I compare that feeling with accidents from childhood and other things I’ve gone through, I realized I always felt that same coldness in similar situations. Instead of fear, there was emptiness and numbness. While I do overload with unnecessary stress in some situations, in moments where intense emotions are expected, I feel this absurd lack of feeling. I even went to a psychologist about this. She said, “you’re overly rational.” The feeling exercises she gave me—experiencing my surroundings, practicing empathy—were unsuccessful. Then I stopped going.

I don’t recall ever having an internal emotional reaction to people’s feelings. I can’t say I have no empathy, but empathy has usually been a matter of conscience rather than emotion for me. For example, even if I can narrate what a refugee goes through or what a child growing up without a family experiences, I usually see it as a logical whole. My starting point is more about observing and copying those feelings, rather than “what would I feel in that situation?” Yes, I think observation is what I do best.

If I go back to my childhood again, I remember this: I generally wouldn’t do harm to anyone. But if I did, if I hurt someone, upset them, made them cry, I never really felt empathy. The wrongness of the act was usually a logical matter. I’d think, “If it were me, I wouldn’t react like this, but since this reaction happened, what I did probably wasn’t very good,” and move on.

My moral sensitivity outweighs emotional closeness. Apart from my mother, father, and sibling, I don’t feel deep bonds with anyone.

When I think about it, my sensitivity to background noise and light is also another clue. For instance, repetitive sounds catch my attention instantly. Whether the environment is noisy or not, my focus gets completely drawn to that rhythm and my mind disappears into it. I noticed this more at work, with the sounds of production machines. While most people can get used to that sound and act as if it doesn’t exist, even a little bit of that noise makes it feel like that’s the only sound in the entire environment, and my attention locks onto it. I’m also strongly drawn to regular sounds in nature. Or when I’m on the phone, the background noises around the person I’m talking to, even if they’re low volume, become my focus point and I miss what’s being said. This is one of the reasons I don’t like talking on the phone. Because I can’t listen, I can’t focus, and therefore I can’t understand.

A similar thing applies to light patterns. Driving in the city at night is quite hard for me because the lights affect me a lot. If there’s rain on top of that, the reflections and all the lights coming from the sides, back, and front sometimes make me feel like I’m not seeing anything other than light.

4. Lessons and Religion

When I think about whether I ever had learning difficulties in the past, what stands out the most is my inability to listen to lessons. Even when I seemed to be listening, I remember constantly daydreaming, focusing on the paper in front of me while the lesson was being explained, trying to solve patterns, and making deductions more from what was written and drawn than from what was said. Classroom environments especially were something that shut my mind down. Private lessons, on the other hand, were the exact opposite. What I remember about private lessons is this: if the teacher didn’t make the lesson fun and interactive, I would disconnect instantly. The best example of this is probably the physics lessons I had with my teacher at the prep school. I was so bored that I basically learned physics on my own just to get ahead of his explanations.

It’s the same in my social relationships. When people talk, I disconnect by the second minute. Especially if I’m not actively part of the conversation. Even if the topic is interesting, it’s like that. The only difference when it’s interesting is that I make extra effort to listen and try to take mental notes. I don’t know if this is an intelligence issue or just high distractibility.

A common misconception about ADHD is the hyperactivity part. It can show up in quiet children too. Daydreaming constantly, being absent-minded, struggling to listen in class, being easily distracted but also able to hyperfocus. Apparently, the biggest difficulties are not hyperactivity itself, but the fast internal communication in their minds and the resulting issues in attention, maintaining focus, planning, and executive functions. I realized I was starting to drift into the trendy “my attention is so scattered yaaa” narrative. Maybe I’m just dopamine-dependent. I don’t know.

Other signs include children who are well-behaved and don’t cause trouble but whose minds are scattered, who forget or skip homework, procrastinate instead of finishing things, miss details, get bored easily, lack motivation, and have random bursts of energy.

Did I experience these? Pretty much always. That’s probably why project management wore me out so much, drove me crazy, and felt so suffocating. When I changed jobs and started dealing with more logical things, the noise in my head decreased substantially. For the first time, I felt like I was doing something suited to my character. Of course, alongside that, the time I spent on garbage content also increased.

Energy bursts are another point. The people who know me generally witness my low energy and the 80-year-old grandpa inside me. So they’re sometimes surprised by the trips I take, the places I go, and some of the activities I do. Even in those activities, I wouldn’t say I’m that energetic, but they are usually things that make me feel alive. For instance, with skydiving—which is something I’ve always wanted to do but never did, and even when I had the chance, I deliberately didn’t do—I don’t think I’d jump screaming from the plane. I imagine it would be more like a meaningless and quiet smile.

I usually live these kinds of things internally. The bursts of energy generally happen at different and unrelated times. A few lucky people have witnessed them. One of them is my sibling, who has listened to my monologues for hours just as we were about to sleep and has seen my meaningless laughing fits (to the point of losing breath). Another one is my ex-girlfriend, with whom I felt extremely natural. She’s witnessed my energy bursts too: laughing fits, excessive talking at random times, punching pillows, shouting for no reason, suddenly singing loudly, dancing with extreme energy, and then, five minutes later, sulking in a complete opposite state of tiredness as if none of it had happened. Of course there have been others who caught different episodes of my energy swings—like my parents, some friends—but partially.

I’m not sure if these episodes are like a split personality à la The Mask movie character, or more like a volcano erupting after tectonic plates have been compressed for too long.

I also put “religion” in the title, because religion is a topic that develops almost entirely outside of us. Something that’s taught forcibly, where you’re forced to form a bond. Even though my family wasn’t strict about it, due to where I lived and basic religious education, there was a time when I tried to form that bond—or was pressured to—and sometimes I just acted as if I believed, simply because everyone else was doing it.

Religious narratives, long sermons, group rituals never interested me, and I never felt an internal bond there either. For me it was a philosophical and historical topic, but I was never truly a believer. For the sake of fitting into society, I had a mechanical relationship with religion. And when I started to be more myself, I had no use for it anymore. I don’t recall ever feeling that inner peace people talk about, or the presence of some extraordinary power, or the fear and sense of safety that supposedly comes with it. In fact, the only thing I remember from the Qur’an courses I attended as a child is how distant and meaningless everything felt to me, the content and the stories. When we went to pray, I don’t remember doing anything other than talking to myself internally. I never felt that sense of belonging—neither logically nor emotionally. And I don’t think I needed to.

5. Visuality and the Problem of Internalizing

When I think of the subjects I learned best, the memories I retain, the things that caught my interest, they’re all related to visuality. There are very few things I remember purely by hearing. Usually, I need to see and practically apply something for it to stick in my mind. True understanding, for me, has always been about system-level logic and the mental snapshots, diagrams, and application memories related to that logic. That’s why I understood engineering later. Many topics became clear in my mind only afterwards. And for the same reason, I used to skip classes to learn. I saw lectures as a waste of time. I hardly attended any class without attendance checks. And with mandatory-attendance classes, I pushed it to the limit.

6. INTP-A and Analytic Cognitive Architecture

On the 16personalities test, my profile came out as INTP-A. Introverted, Intuitive, Thinking, Prospecting. The most prominent traits of this personality are abstract thinking, individuality, freedom-focus, low social contact but high depth of ideas, system solving, and direct communication. Their strengths are being analytical, original (i.e., creative), open-minded, curious, and honest. Their weaknesses include escaping crowded environments, being detached, being insensitive—in the sense of finding emotions, affection, etiquette, and traditions illogical. Dissatisfaction and overthinking. This makes it hard to take action and leads to trouble making decisions. Another weak point is impatience.

These types of people can also be called “confident individualists.” They like being independent, working alone, having low emotional needs, and enjoying silence. When I read this analysis, what I thought was how much it overlapped with me. Of course, identifying with the result might be a bias—a self-confirmation bias—but unlike AI, these tests are not trying to reflect your thoughts back at you.

In short, having this kind of character and perspective is not inaccurate in explaining some of my behaviours. Maybe there’s no need to look too hard for a neurological disorder or difference.

7. Career Skills and Overlapping Analyses

I’ve never been someone who gives up easily, but I’ve also never been someone who clings to something with passion and devotion. As I wrote before, I’ve never had intense emotions about anything. Naturally, in my professional life too, even when there were things I didn’t want, I tried to get the best out of them.

During the five years I worked as a project manager, my daily routine consisted of meetings, communication that required emotional intelligence, chaotic flow—in other words, uncertainty. There was a constant flow of verbal information. I constantly had to manage people, empathize, and be patient. I don’t think I did a bad job. Because I created certain profiles and patterns in my head. I logically analyzed what I was experiencing. My communication was seen as clear yet sensitive. Inside, though, there were storms.

That’s why, for those five years, the things that caught my attention the most were my low energy and the fog in my brain. Work life felt like a theatre hall and I had a different mask. I wore that mask as required by my role. My focus was always scattered. Sometimes that was an advantage, but most of the time it was a disadvantage. I couldn’t follow plans or I would lose interest quickly, and I was constantly tired. Especially my social energy. After work, I didn’t even want to talk to a single person.

I mostly attributed this to work stress, my longing for engineering, and the feeling of being an outsider. I even mentioned this many times in my blog posts. But when I looked at other people, they seemed to handle everything so much more easily than I did. And when I met others who went through similar things, I noticed they didn’t seem as overwhelmed as I was. Was I really exaggerating, or was there another issue?

Of course, my engineer brain wanted to solve the system. I tried to satisfy that hunger by analyzing and modeling people’s behaviours and habits. My search for a regular and logical workflow, and my nature that also resists too much order, somehow seemed to fit planning and project flow. I usually tried to keep meetings and communication to a minimum. Engineers liked me for that reason. However, my abstract thinking, lack of technical analysis in the job, and above all the social and emotional load were extremely excessive for me. When I realized this, I started feeling more and more that the problem wasn’t the job itself, but the mismatch between the nature of the job and my own nature.

When I changed jobs and went back to engineering, I realized that project management was extremely incompatible with my character, my routine brain functions, and the habits I’d had since childhood. Now my job is more about technical analysis and problem-solving. The social load is less, and naturally so is the noise in my head. Most importantly, the brain fog is completely gone.

8. Doubts About Myself

I don’t think I’m stupid, but am I intelligent or just a dreamer? Am I talented or drowning in inconsistency? Am I realistic, or am I drifting away from reality while wrestling with abstraction? Is my attention scattered, or are these excuses? Or am I just lazy? If so, why?

These questions occupy my mind a lot. For example, when I ask myself “am I lazy?” and try not to be, I see that I get stuck somewhere. Yet I’m known as a laid-back person by those around me, but not as lazy. Similarly, all the work I’ve done to tackle my distractibility helps up to a point but then stops working.

Ideas are constantly flying around in my head. Even for ordinary tasks, I think of different solutions and routes. When I share this with people, I get responses like “I couldn’t do that,” “I’m not that multi-directional,” about things I thought were normal. I guess that’s a sign that I’m doing some things differently in a good way, even if I don’t notice it or doubt it. My bigger problem seems to be sustainability.

I think the reason I like alcohol and sometimes drink too much when I don’t logically restrain myself is also this. I enjoy life slowing down, thoughts becoming blurred, my mental clutter breaking into tiny pieces, and then that stream of thought coming to a stop. Sometimes I desperately need that.

I’m not sure what all of this means, but I tend to view it more as neural diversity. The reason I’m writing this piece is actually a kind of thinking out loud, getting the thoughts in my head out. I’m trying to understand how normal or abnormal all this is.

Even while writing, many memories and ideas came to mind. I found partial answers to many questions, like why I couldn’t listen to lessons, why I avoided crowds, why I constantly felt a heavy load in social relationships, why I kept starting projects and not following through, why I found peace in solitude, why I couldn’t form emotional bonds, why I felt burnout in project management, and why my mind felt more open after my last job change.

At the very least, I did understand some things clearly throughout this entire thought process.

For example, the biggest reason for the occasional energy fluctuations I experience is probably mental processes rather than character. As is the indifference I feel toward many things, contrasted with the out-of-place emotional outbursts I display in unrelated contexts. Like wanting to laugh and burst out laughing during stressful or serious moments. Like suddenly shouting songs at home and then, a few minutes later, sinking into a silence as if none of it ever happened. Like being extremely disturbed by changes to my routine, while also being bored by the routine itself. Like overreacting to moving objects and people’s movements.

So my “compressed plates” approach felt more accurate. I don’t know its psychological explanation, so a geological metaphor suited me fine.

Sometimes I find the outside world overwhelmingly intense. I actually see this piece as an escape from that intensity. In the end, it didn’t lead anywhere. It didn’t need to. Other than waging war against data privacy by giving away every possible physical, mental, and psychological detail about myself, I don’t think it will serve much purpose.

I think of it as a bout of late-night rambling. A feeling of meaningless talking and expression.

Conclusion

The conclusion I draw from all this is essentially this: even though there were many clues that could supposedly have been “noticed in childhood,” survival instincts took precedence and I somehow managed to cover up the mismatch with masking. That’s now affecting my current life in different ways. I still partially mask, partially let the rebellion inside me grow, my tolerance decreases, or I simply accept the mismatch more.

Some might say “just let it go,” “don’t overthink it,” but those are usually the phrases I react to the most, because not thinking feels like dying to me. Filling the mind with trivial things too.

I don’t process many things the way “everyone else” does. At the same time, I’m aware that I’m generalizing “everyone” as well. Clearly, everyone has their own unique mental processes.

One of the best decisions I seem to have made was quitting my previous job. That’s the clearest result of the analyses I’ve done and the reflections I’ve had about myself. Job–character fit matters. On this, I think I was right to feel “misunderstood.” It was more than just ordinary work stress. It was a conflict strong enough to render even my strategy of adapting to the environment and suppressing the mismatch ineffective.

It also gave me an idea of the roots of the problems I’ve had in my relationships so far. It clarified a bit why I love some things and stay distant from others.

I’m not really arriving at a conclusion, actually. When I wrote this, my goal wasn’t to put myself into a category. And that’s how it turned out. It was more of a self-critique aimed at placing my sense of self on the right foundations and a process about accepting myself more.

Leave a comment