Elephants have been used for centuries for transportation, carrying loads, construction, and war. Even today, they are still used for similar reasons. Beyond that, they have also been used for entertainment—in circuses or zoos.

Do you think this was voluntary?

Of course not.

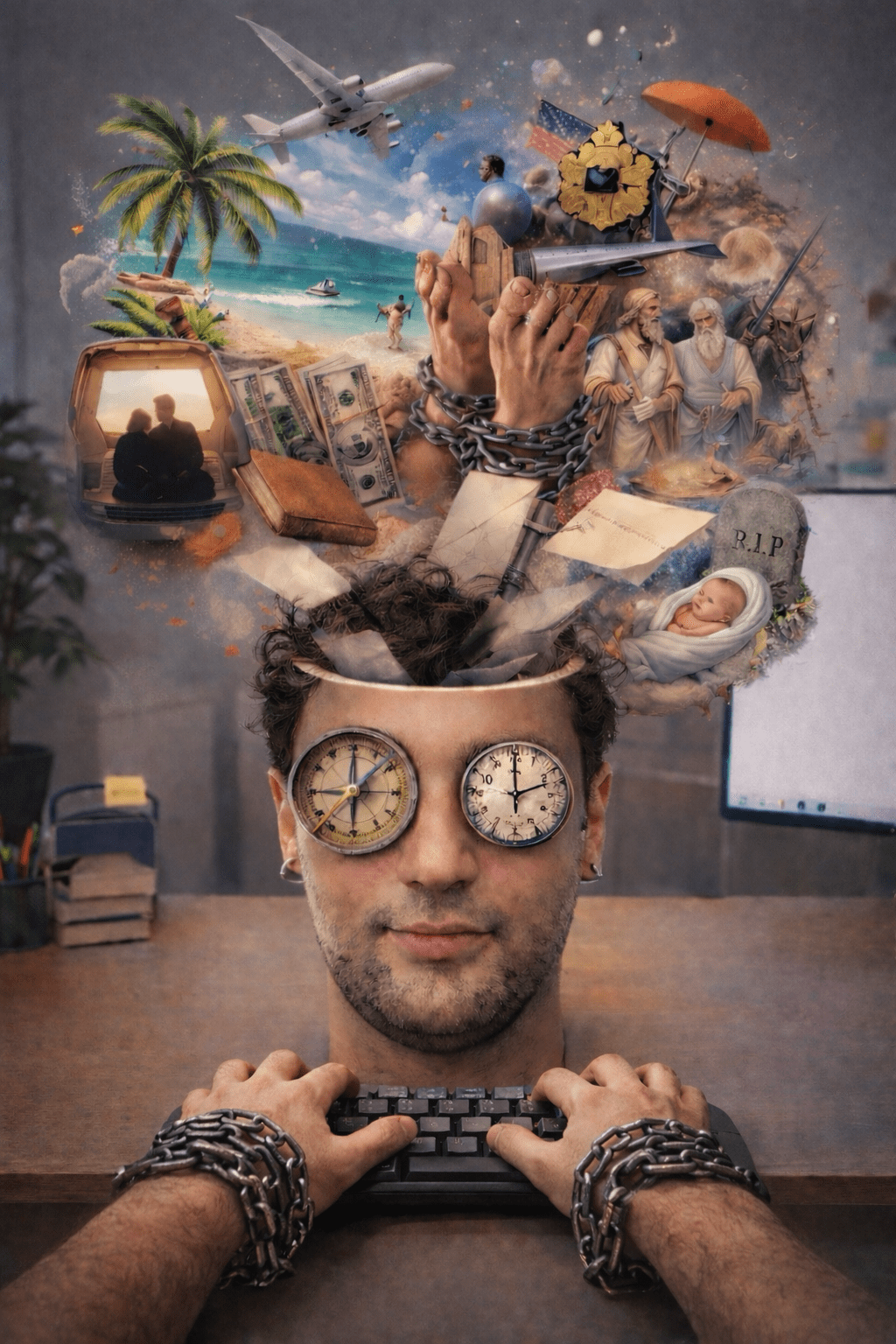

The way to make elephants “useful” is to chain them when they are young. Their legs are tied, and they are kept captive for weeks. At first, the animal resists. It tries to break the chains and escape. It screams, runs around desperately—but in vain. The price of trying to escape is torture and punishment.

Weeks pass, and the chains are replaced with ropes. Because of the feeling of being bound and the pain it has experienced, the elephant no longer tries to escape. Memory overtakes reason. Over time, the rope is removed too. Then the cage. But the elephant still doesn’t run away. It has completely erased that impulse and replaced it with the thought: better not take risks. The possibility of pain grows larger in its mind, and it becomes a docile elephant.

The brain of a young elephant, just like that of a young human, is neurally flexible and desperate to feel safe. It generalizes experiences instantly. A brain fed by fear accepts the safest option as the correct one.

Isn’t the same true for humans?

For the previous generation, having a stable job, a warm home, and a proper family was important—because their memories were filled with war and conflict. For their children, what mattered was education and knowledge, because education and knowledge meant social security. Job guarantees and above-average status. Today, however, the situation is different.

You can also think about this politically. Alongside all this memory, wasn’t the fear of “instability” planted into people’s minds—especially after the Cold War? Now look at the countries where people say “we need stability and order rather than instability.” Almost all of them ended up with dictators. They used both the fear of instability and the fear of not owning a home, of not being able to cook food in your kitchen. They interpreted a wealthier world as the result of stability. Because of the fears of the 20th century, people gave up their freedoms. Just like elephants.

But I want to focus less on politics and more on modern life. There is a joke by the world-famous comedian Louis C.K.about vocational schools. He says they are places where dreams are reduced to five. While children grow up being told, “You can be anything you want in life,” vocational schools say, “We’ve narrowed that down to five options for you.”

Isn’t it the same for us? You can do anything in life, have every opportunity—but every education we receive reduces our imagination and desires by at least 50%. In the end, what remains is your profession. And even that isn’t enough: certifications and experience reduce it further, until you finally become an “expert.”

Isn’t there something strange about this?

Some say there isn’t. Then another question arises: do you think you’re getting what you deserve for your work? When the decisions you make can create million-dollar differences, is the 2–3 thousand you agree to really satisfying? Does it compensate for the stress that keeps you awake at night, the hunching of your back, the future healthcare costs, the moments you miss with family and friends?

But I think something even more important is this: is it worth it for your own brain to be so constrained, for your dreams to dull, for the flexibility of your mind to die?

My answer is no.

Today, we have opportunities that previous generations couldn’t even dream of. We live longer, we are safer (even though the world has been full of wars lately), we are healthier. We can access information instantly, connect to the world with a single click, and even in our loneliest moments, flirt with someone on the other side of the planet.

We’ve even reached a point where machines can do many jobs for us, make decisions on our behalf, and complete tasks that used to be difficult in seconds.

Logically, we should be happier, more motivated, more hopeful. Yet we are stuck in a strange contradiction. We are living in better conditions, but our desire to live is lower. We appear freer, yet we feel more trapped.

Under normal circumstances, we should be working less and feeling less exhausted. Instead, we work more intensely. Our workload doesn’t decrease; it increases. The mental junk entering our brains multiplies, and our mental fatigue is greater than ever.

Evolution

Contrary to thousands of years of evolution, modern life creates anxiety and stress—because life has accelerated enormously. Keeping up with this pace is difficult.

To keep up, we drink coffee, set alarms, create reminders. Where there is no depth, we have to stay constantly alert. Isn’t inner burnout natural? Our battle is with ourselves. With our nature.

Captivity

We grew up chained, like a young elephant. This reminds me of a story told by Ferhan Şensoy.

After being selected for theater auditions in Paris by a jury of the world’s most important theater figures, Ferhan Şensoy tells his father that he wants to quit architecture and become an actor. His father replies: “Mind your business. Is there anyone like that—some vagrant—in our family?” Ferhan Şensoy thinks and says, “Why shouldn’t I be the first vagrant in the family?”

That’s exactly the situation. We’re stuck between the base and the middle of Maslow’s pyramid. Our fears take over. From childhood, we are told to acquire a good profession. “What will you be when you grow up?”

Finish school, then we’ll see. Get your diploma, then you’ll decide. Get a job first, then you can think. Isn’t it time to start a family? Now you’ll have kids. The kids grew up—have you thought about retirement?

I think retirement is the only time when someone can say, “I’ll see what I’ll do, wander around a bit, and find my way accordingly.” Because everyone knows what the next stage is. Zero.

Isn’t school the same? Those who step outside the order are punished. A child who is good at sports is punished because their grades are bad. A child talented in music is praised, but with the footnote that they must also study their lessons. We are told to read books—but even which books are allowed is restricted. Then come exams and dozens of useless pieces of information. When in fact, learning logic alone would be enough to become something in life. But everything except logic is taught. And then, of course, people say, “I don’t remember anything from my education.”

Now it’s even worse. Hand them a tablet and move on. Stuff their heads with ridiculous nationalist rhetoric, feed them sugar—and if mainstream television is on at home, God help them.

When you think about it, none of this is illogical. There is a system, and the system has to function. Some will be managers, some engineers, some workers. What feels strange to me is the reduction of freedom. I’d be lying if I said I don’t envy shepherds in the mountains, ancient philosophers, or heirs who don’t worry about money. Sometimes I even envy factory workers. They go home, drink their beer, and don’t think about anything else. Those who think less often think more freely.

With current technology, I would expect us to work less. Three days, for example. Or three and a half. Production models should change. Less human labor, less exploitation, a fairer life. At the very least, basic needs should no longer be tools of fear. Everything else could be the return of personal effort. Ambition is part of human nature—everyone cannot be equal. But at least those who work hard could get what they deserve, while others wouldn’t have to worry about what they’ll eat in the evening.

We no longer have chains. Like elephants, we left our cages; our chains were cut—but now there are calendars. There is no whip, but there are notifications. There is no master, but there are expectations.

You can’t free yourself from basic fears. In developed countries, there is at least some unemployment or income support. In many places, this doesn’t exist or is insufficient. So the same cycle keeps turning. If you work, you own. If you own, you must consume. And you must always be reachable.

Our own dungeon.

Growing up with the lie “do what you love,” only to realize that work is not something to be loved, is one of the most heartbreaking realizations. While technology can create enough resources for the entire world, we still have to worry about rent and bills.

We think we are free because we make choices—but most of our choices are compulsory.

Perhaps the only difference between us and slaves is that we are not subjected to physical violence. Though even that is debatable. Violence doesn’t have to be physical.

That’s why I call it captivity. We are more captive than ever. And we don’t rebel, because we learned the price of rebellion from infancy. Those who dare are labeled terrorists or anarchists. Just like a soldier who doesn’t want to shoot—wanting something natural is seen as a disease.

In the end, as we slowly empty inside, we ask, “Why am I unmotivated?” and finally conclude that the source of the problem is ourselves. That, I think, is the system’s success.

Fatigue

Comfort was once a goal to be achieved. Now it’s a huge trap. Because the price of comfort is contradicting yourself, drifting away from your values, and accepting everything that conflicts with them.

It’s a trap because everything is easy, fast, and effortless—and therefore meaningless. When you can instantly access everything you need, you no longer see the labor behind it. Desire weakens. So does empathy.

I used to give a similar example about veganism. Anyone with conscience and ethical values should be vegan. For that to happen, people would need to personally experience every stage of how animals are turned into packaged products. I’m sure that if every individual were taken to animal farms at least once, meat consumption would drop dramatically.

The same applies to labor. No one wants their child to work in industry at the age of ten. No one wants them to spend half their life in dirt and grime, waiting to die in pain later. But that’s exactly what happens when we buy our favorite jeans. That’s the cost of ordering dozens of items just to follow fashion.

While walking the streets of Istanbul recently, I came across a child collecting cardboard. He couldn’t have been older than fourteen. If he was, the story is even sadder. He was about to turn left; I was walking on the sidewalk. He moved toward a trash bin beside me—I didn’t notice. We almost collided. He said, “Sorry, brother,” and gave way. I thought about it for a long time. There was nothing to apologize for. I should have been the one apologizing. I should have been the one giving way. While I was thinking about the strangeness of it all, the sight of that child pushing a cart uphill at that age—and everyone accepting it as normal—disturbed me even more. That’s the kind of world we live in.

In such a world, we lose meaning. We forget why we live.

I don’t think being depressed is wrong either. When someone says, “People are dying all over the world—are you really worried about work?” that argument angers me. Because those people who die, those children forced to work, are paying the price of the same world that makes us depressed, unmotivated, and afraid to rebel.

The comfort trap exhausts us. Living with forced choices and being in constant conflict with yourself is exhausting.

Freedom

Freedom is not infinite options—it’s making a meaningful choice in your own way.

What we’ve lost today is the meaning of choice. What suffocates us is the superficiality of our choices.

We have many options, but most of them are shallow. We choose, but we can’t commit. We start, but we can’t continue. This returns as lack of motivation. This is not laziness. If it were laziness, it would at least be more meaningful. Many inventions and developments in the world were born out of laziness.

Hedonism

This, too, is a way of escaping the feeling of captivity. Maybe that’s why social media became so popular. Platforms where you can do everything gave way to platforms where you can only write, only fill a certain number of characters, only share photos, only post momentary images.

Maybe that’s why people started making money by undressing. Is it meaningless? Considering captivity, not that much. Why is selling naked photos—selling your body—shameful, while selling your entire life to companies is not? Ethically, they’re not that different.

Why are drug parties condemned? For those people, it might be an escape. Is it shameful to live life as they want, or are people really worried about their health? Or is it disturbing to see them envy the lives they read about in the news? While someone can’t find bread, another travels between realms. “It encourages people,” they say. Aren’t social media influencers more dangerous than drugs?

And alcohol? Isn’t it also an escape from captivity? A moment of relief from all worries? Just like cigarettes. Alcohol is not shameful. Have you ever seen people condemned because they drank alcohol and partied all night? No.

The sad thing is this: you either accept captivity, or you become a hedonist and stop caring. Is there no middle ground? There is. But like the baby elephant, we closed that door in our minds years ago. If I think, you don’t. If you think, someone else doesn’t. The middle option seems to not exist. Either you’re an anarchist or a good citizen. Either you’re with us or against us.

Life

The problem is not us—it’s the life we’ve built. The life we were taught. The life shaped by the technological transformation we happened to encounter.

This is our generation’s biggest dilemma. Everyone is unhappy with their job and life. Some accept it and, even knowing they’re fooling themselves, try not to show it. Others have simply given up.

Measuring the return of effort is difficult—especially when comparing physical and mental labor. For some, sitting in an office all day, running from meeting to meeting, seems easy. On the surface, it looks like just sitting and talking. The reality is not that simple.

Still, I don’t see lack of motivation as a negative feeling. I see it as an opportunity—within forced choices.

What we all want is the same: to live better, to live healthier. But what does living better mean? That’s the real dead end.

Is living better driving to work every day, owning everything you want, getting promotions, earning a lot of money, being praised, always having the best? Or is it not wasting, considering the environmental cost of the fuel you use, living accordingly, avoiding consumption as much as possible, not chasing trends, staying away from showiness?

That soldier who doesn’t want to kill comes to my mind again.

In my daily life, which often contradicts my personal values, the only solution I’ve found is slowing life down. Being offline. Avoiding phone calls. Reducing the stimuli entering my mind as much as possible. Focusing on slow tasks. It may not be freedom—but at least it feels real.

ChatGPT can make mistakes. Check important info. See Cookie Preferences.

Leave a comment