Exactly 21 years ago today, one of the events that changed the way I look at lifeö perhaps the very first. took place.

For the first time, I saw how people I had perceived as solid and unshakable in childhood could be completely shattered by an unexpected blow. I saw everyone at their weakest.

I was 14 years old then. On one hand, I was trying to make sense of what was happening. It started with a phone call. an anxious voice. It meant nothing to me at first. I simply went back to my game. Then came the panic at home, the worry, and the house slowly filling with people.

Panic, anxiety, curiosity, stress. and finally grief.

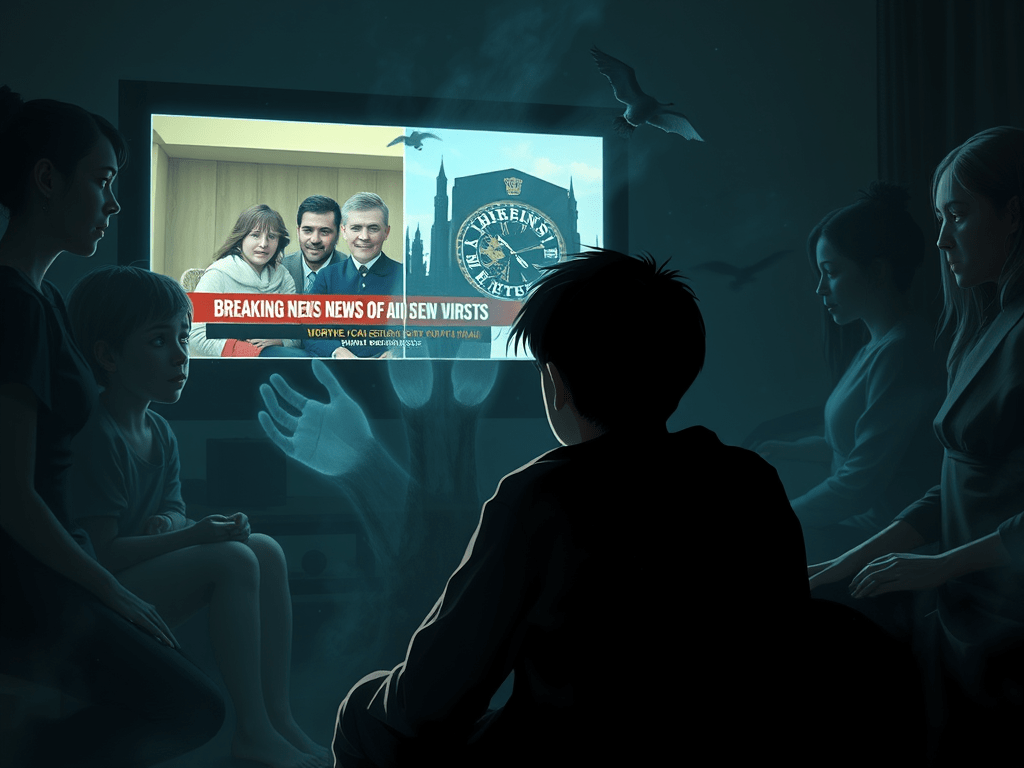

Living through all of this while trying to follow breaking news on television makes the experience even stranger. You live absurdism at its peak. Between light-hearted TV shows comes the long-awaited painful news; while searching for seriousness in the news, you see politicians celebrating the EU negotiations, and at the bottom of the screen, a scrolling headline about the attack.

The news says that some escaped, that some survived. You wait like someone waiting for Godot. Maybe it’s him. Your insides churn. Then an image appears. The worry in the eyes gives way to helplessness. With a child’s mind, you tell yourself, no, it’s not him—but doesn’t a person recognize their own family? You know. My father recognised his brother quickly. I saw that there is no hope anymore.

A cold settles inside you. What reaction is even possible in a moment like that—especially when everyone around you is crying? What follows is predictable: a state ceremony, insincere condolences, and the funeral. As if those who were celebrating the day before were entirely different people.

The funeral is even stranger. Love, respect, and pain coexist. Still, it feels like a surreal painting. Even if the world collapses, most people will brew tea the next day just as they always have.

Two things I will never forget: the faces of everyone I knew—and the words people used about me, saying that I was “living the pain inside.”

I was feeling something inside, but was it really pain, or the effort to make sense of this surreal scene? There was some coldness in me, some anger, and a sense of meaninglessness and emptiness brought on by sudden disappearance. The other feeling I couldn’t name must have been grief—because even 21 years later, writing this makes my eyes fill with tears.

One thing that struck me as strange was the insistence on order. Trying to squeeze even the most natural reaction—screaming, breaking down—into a controlled framework. Even then, I thought: the one who dies is the one who escapes; the real burden falls on those who remain.

Once a person is gone, what is said about them no longer truly matters. The void left behind fills over time—but not with truth. Fantasies take over, emotions blend together, and manipulated stories replace reality. A mythologized version of truth.

Especially when a death you followed on television resurfaces years later in a YouTube video, people expect a great heroic story. That is the only way it becomes bearable.

We sanctify death. When the fire falls into our home, we demand an explanation, a meaning. In truth, we create our own legend. Perhaps this is the most effective way of coping with death.

Reality, however, is entirely different:

another body spent by politics without a blink—cold, calculated, indifferent.

When similar events occur, it all comes back. In 21 years, thoughts change, but feelings remain. One thing never changes: the formulaic sentences and grand words spoken after every body that is sacrificed.

What happened in 2004 was not just a loss—it was the day my view of life changed.

It was the first day I truly accepted annihilation. They told me, “Remember him as the last time you saw him.” I still do. But sometimes I wonder: if none of this had happened, would we have had a healthy relationship, or would we have drifted apart anyway? Maybe the last image I remember—and the fantasies created by memory—aren’t such terrible things after all.

Still, people search for heroism. But isn’t heroism often just paying the price for others’ foolishness? Aren’t all those symbols of national pride borrowed from history simply payments of a cost—of mistakes?

I still can’t decide which is worse:

the absence of a true legend,

or disappearing on behalf of others,

or believing in legends invented by ourselves.

Memories are like a door between life and death—a one-way door.

While keeping the dead alive,

they also keep the living tied to life.

Leave a comment