I have travelled to many places and liked many of them, but Bilbao felt strangely warm. More like a place to live than just to visit.

Since it was November and in the north, I can’t say it was a typical Spain trip, but the city’s reserved warmth — more serious than Spain’s Mediterranean coast, yet just as embracing — was deeply impressive. The sincerity and friendliness in the cafés and restaurants, the staff who welcomed me on my second visit as if I had been hanging out there for years and chatted with me for a long time, and the support for my Duolingo-level Spanish were all highly motivating. I think the soul that Germany has drained out of me had missed this warmth and sincerity.

Bilbao is a small city, even though it looks bigger than it is. With its port opening to the ocean and its ironworking past, it would not be wrong to call it a trade and industrial city. Unlike typical tourist destinations, the city doesn’t immediately pull you in with its art or colors. My first impression was that it felt like a mix of Ankara, Mersin and Trabzon. As I walked through the city, what I noticed wasn’t the architecture or the beauty of the city, but the flow of life. Looking around a bit more, the architecture and art tucked away in various corners, just like its nature, also caught my attention.

One of my reasons for going to Bilbao was that I had never been to the Basque region before, but the real reason was the Guggenheim Museum. Especially after Dan Brown’s vivid descriptions, it had grown even larger in my mind. I was not going to be Robert Langdon, of course, but that’s the nice thing about life. Every step we take becomes our own unique experience.

When I arrived, I stood there staring at the building for a long time. The soft curves of the structure, its fluidity, and the harmony it created with the city were mesmerizing. I wasn’t drunk or high; the building truly was fascinating. It carried contradictions within its harmony. I first went there in the late afternoon while walking through the city. Did the heavy rain soaking my already sore feet affect my feelings? I think yes. It was beautiful at night and just as beautiful by day.

It felt as if the building itself had sent me a message. The next day, the puddle that I had stepped in without noticing the night before — the one that soaked me up to my ankles — had been cleared, and warning signs had been put up. “Water may accumulate here, be careful.” Maybe they had watched me on the security cameras the previous evening, laughing as I tried to avoid the water and ended up stepping into it even more.

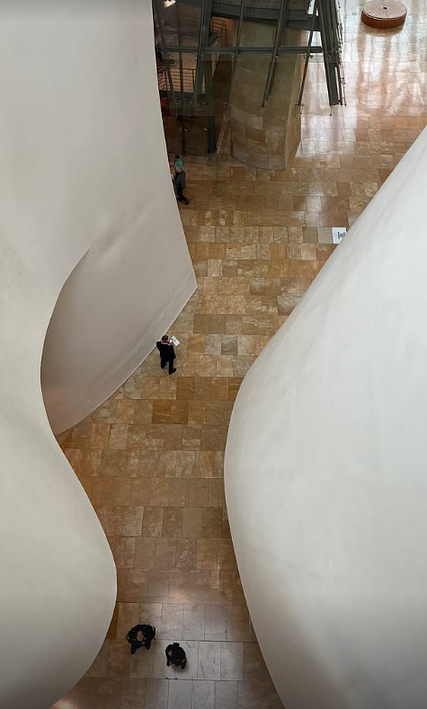

The next morning, the first thing I did was go back to see it in daylight. Usually, the interiors of places that look this impressive from the outside end up being disappointing. That’s why, as I entered, I thought, “I’ll probably see a couple of paintings, a few artworks, and leave.”

Of course, that didn’t happen. The simplicity of the interior design was at least as impressive as the exterior. The exhibitions inside seemed to shout, “We’re here too.” It was incredibly inspiring. When I left, I found myself thinking about my existence, my materiality, and the meaning and importance of art. Art was a philosophy, a cry, and a way of expressing oneself. But more importantly, all the things we see as negative or ugly were being dissolved through art. My mind had travelled from Idlib to Palestine; from refugees drowning in the Mediterranean to ruthless fascists, from indifferent people to the most forgotten corners of the world. It felt as if time had stopped.

I also thought about social pressures and the absurd norms of the communities we live in. Instead of spending a lifetime trying to conform to somewhere or something, it felt like watching the tangible advantages of originality and being yourself.

Mark Leckey’s words covered the walls. On the one hand, he talked about dimensionlessness, about how we cannot be confined to a single space, and about humans existing somewhere between matter and soul. The dimensionlessness in his sculpture and his view of cities explained everything. On the other hand, he described how music affects us physically while remaining something abstract.

Yayoi Kusama’s mirrored room was something else entirely. Simple yet powerful. I watched my own reflections among the lights for minutes, feeling as if I were in an endless universe. Do we gain value as we multiply, or is what we call value just an illusion?

And then El Anatsui’s metal waves… That giant “carpet” made from collected caps was essentially a summary of thousands of lives and the stories they left behind, stretching from Africa to Europe. At the same time, it was a reflection of all the suffering and pain we choose to ignore. On one side, there are people like us who complain about rough seas; on the other, there are the bodies washed ashore by those same waves. How else can one better express the cruelty of a world where we can’t even tolerate a wrinkled bedsheet?

A strange contradiction. In the midst of all that depth, my thoughts suddenly shifted to the fact that I was on holiday, and my mind drifted off to pintxos and torrijas.

That’s what I love about modern art. The way it presents depth and hunger is powerful enough to affect even someone like me, who jokingly calls himself “an art idiot.”

As much as I liked the Guggenheim, it would be unfair not to talk about the Fine Arts Museum. There was a Georg Baselitz exhibition when I visited. The figures he turned upside down were a bit disturbing but thought-provoking—as if saying, “Maybe the real problem is in our point of view.” Other artists I, as an art amateur, got to know there were Darío Urzay, Jon Mikel Euba, Benlliure, Aresti and Ibarrola. Each of their abstractions, the way they presented their work in a way that makes you question the essence of art, and their political energy, all seemed to shout that what really matters is not aesthetics but conscience. I don’t believe that anyone with a conscience can stay silent in the face of injustice. I don’t believe that anyone with a conscience would hide behind cities, countries or identities. And again, I don’t think anyone with a conscience can look at the world through categorical lenses. The world we live in, on the other hand, is one where we constantly run away from ourselves; where greed stands in front of conscience. Everything feels fake. The struggle Spain is going through right now is exactly this: a struggle between those who can simply be themselves and those who insist, “You will be like us.” It’s one of the rare places in Europe where the “either be like me or die” mentality hasn’t fully won yet. A very valuable struggle.

While wrestling with these thoughts, I also realized this: the strangeness of modern art, the chaos alongside its simplicity and power, appeals to me much more than classical fine arts, which are more abstract and more distant to me. Maybe this feeling simply comes from the fact that one aligns more with my engineer’s mind and feels more “doable.” The other’s abstraction and distance make me uncomfortable—yet even that discomfort is enough to make me admire it.

Outside the Museum

Even while writing about it, I feel lost in a sense of timelessness. When I finally put down the last full stop, I felt like I could finally leave the museum.

When I stepped out into the streets of Bilbao, I realized that the calmer and more human version of the chaos I had experienced inside the museum was already flowing through the city itself. Unlike many popular European cities, the city was modest and self-contained. The buildings, bridges and river existed in a strange harmony, and at the same time, many contradictions coexisted. The people felt the same way: in their own world, cheerful, unpretentious, yet not detached from reality.

One of the things I liked most was the bar culture. The café/bar concept feels like it was created for socializing. A kind of socializing that doesn’t overwhelm you. These are places where you could technically stay from morning to night, but are at their best after work — when you can either sit with your friends or with strangers in the same space, chat a little and have something to eat. Like a glass of frothy beer: a place that relaxes you as it pours. Places where time stops and tension melts away.

To be honest, because of the Basque history I knew, I expected the people to be more tense, or like in Catalonia, more dominant and perhaps more closed towards foreigners. It was not like that at all. There were similarities, yes. For example, Athletic Club Bilbao is not just a football club, but an identity. It is intertwined with the city’s identity and history. Everywhere, Basque was written alongside Spanish, but as they told me, due to the history of dock and iron workers, there wasn’t much of a “you’re not one of us” attitude. Naturally, that also meant less pressure around belonging. However, they did say that in recent years, Basque culture and language have been brought more into the forefront.

Apart from that, as in the rest of Spain, they have taken a stance against tourists and don’t really like them. On this point, I agree with them. I think tourists should stay outside the city. There could be something like a “tourist village” where they stay. They should only come into the city to visit and see. And touristic businesses should also have limits. Every place turning into an Airbnb, a tourist restaurant or a tourist-clown venue doesn’t just damage the local economy, it also disrupts the cultural fabric of the place. Everywhere starts to look the same. And for the locals, it becomes unlivable.

I thought about this in a fishing town I visited. Now the place is “valuable,” filled with tourist-only restaurants, fake cultural elements and apartments reserved for tourists. “Valued,” they say… Yet once, in that fishing town, people simply lived as they were—without ever thinking about the “value” of where they lived.

The “You Could Live Here” Feeling

In many places I’ve been, I’ve thought, “People really live well here.” Sometimes I felt a bit jealous, sometimes I thought, “It wouldn’t be bad living here.” But I think Bilbao is the first city that could actually answer the question of “If I were to move somewhere, where would I go?” For me, it’s a small city, but it doesn’t feel boring at all. It’s small, yet there was life in every stop I made. Every stop had a square, and around that square, there were places to eat and drink, and of course, people.

And not just that; there are mountains, the sea, culture, music, nightlife, daytime, and a lot of warm smiles and eye contact. In other words, people who don’t avoid each other. Even with my basic Spanish, I was able to have small conversations with many people, young and old. This place definitely gave me the impression of being a city one could truly live in. Living here feels like living life in a simple yet full way. Not too much, not too little. Just the right amount. Of course, all these positive feelings exist alongside economic realities.

Time to Return

As I was leaving Bilbao, I realized something: despite the rain I battled throughout the trip, my feet being sore and bruised, all the walking I did and the long journey, I didn’t feel any fatigue from those four days. It was as if I had been on holiday for a long time and at the same time as if I had just gone to visit a friend living around the corner. It was a trip that rested and motivated me. The calmness of the city and its liveliness were both striking. The smell of the sea that I breathed in was a bonus I had missed—a feeling that made me feel alive. Once, at the Strait of Gibraltar, I thought, “This is the gate Hercules opened to the world; it’s also the gate that opens me to distant seas.” A year later, I had found myself in Colombia. The feeling Bilbao gave me, on the other hand, was balance and calm. At the same time, serenity. Even though it pushed me into the depths of existence, it didn’t drag me into the heaviness of existential dread; instead, it nudged me towards a kind of joy that makes you love life as it is. It reminded me of the importance of joy alongside aesthetics. It made me feel that true aesthetics lies in the simplicity of life.

Like an old friend, Bilbao accepted me as I was, without imposing anything on me. Just as I try to look at the world.

© 2025 Bahadırhan Çiçek. All photos belong to the author.

They may not be used, copied or reproduced without permission.

Leave a comment