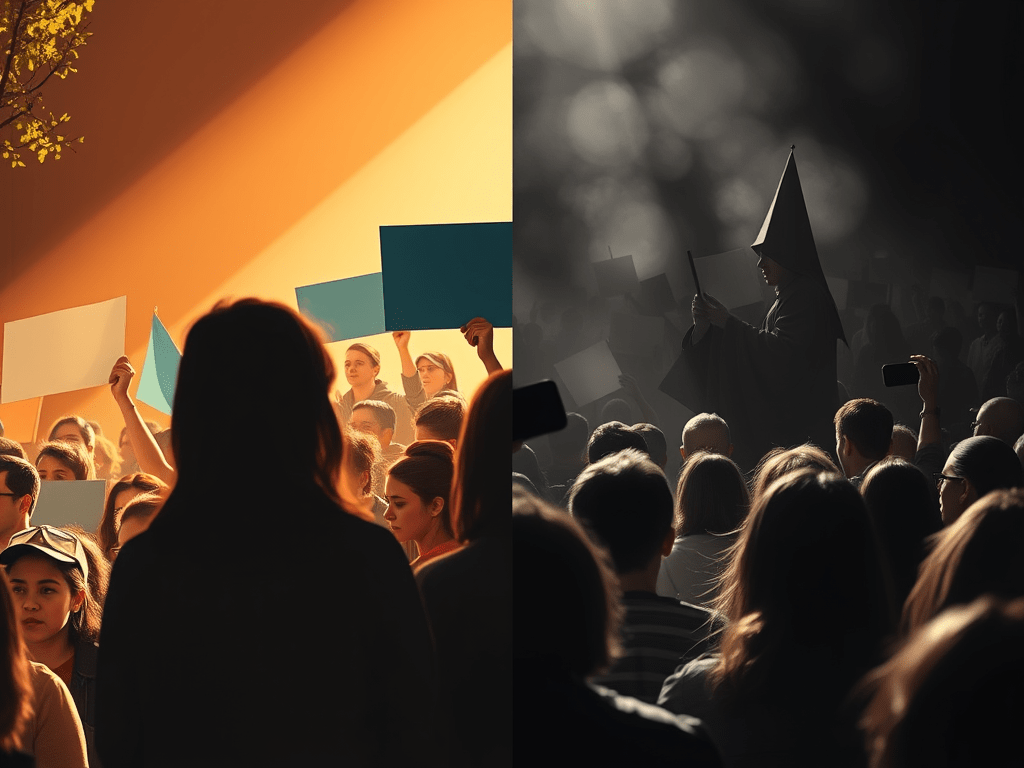

I guess it’s the same everywhere in the world. People have split into two poles.

Even the strongest democracies have been reduced to the level of “protect the ballot boxes.” Participation in democracy is now measured simply by the number of people who vote.

One pole is socially conscious, striving to make the world a better place, fighting for the representation of every individual — yet in doing so, often blindly supporting anyone who utters the right magical words, whether they are good or bad.

The other pole feeds on 20th-century habits and outdated views, transforming them into a massive power through technology. This side hates everything social, sees people not as individuals but as faceless crowds, sells dreams, ignores the dangers of people’s thoughts, gives them what they want to hear, spreads misinformation, does anything for money, cares only about power — and receives blind support for this image.

This year, municipal elections were held in Germany. The racist party under constitutional surveillance gained more support than ever, securing a notable share of power. It has cemented its place as the second or third party whenever elections and coalitions are mentioned.

This party is against women participating in the workforce, against them having rights of any kind. Against immigrants. Against social policies. Against children’s education. Against teacher training and support for schools. Against environmental protection. They want to raise the retirement age. They are against workers’ rights. Against rent controls. Against agricultural support. Against aid for the poor, against freedom of expression, art, music, and aesthetics.

The same party, on TikTok, tries hard to appear fully democratic. In my opinion, they fail — because anyone who can read subtext quickly understands what they actually mean. But the masses who treat politics like a game and don’t know what they are voting for fall for this act.

The side they fight against is the exact opposite: it supports social policy, welfare, education, freedom of expression, critical thinking, and simply being human. They are not chasing social-media spectacle, because they trust people’s intelligence. And yet, the results speak for themselves.

When you tell it this way, the typical criticisms and memorized slogans come: war, arms aid, globalism… Hard to grasp. The same thing is happening in the U.S. The same thing has been happening in Turkey for 20 years. Media manipulations and social media — they work all too well.

It frustrates me that in any country, someone who calls global warming a lie and turns their back on science can be allowed to govern anything, let alone a country. It frustrates me that people whose minds are poisoned with conspiracy theories get to do so.

Similar debates exist in many countries. Many people ask: where did we go wrong? Where in education, where in development, did we fail, that the democratic values which emerged after so much trauma have led us here — split into two camps?

How did something so naturally fragmented and fragile end up in a race against a hardened, unshakeable bloc that approves any nonsense? This alone shows the issue is no longer local but an international problem.

It feels like humanity is moving backward.

On one side, a generation that doesn’t want to work, chases easy money, fills its mind with social-media and cinema junk, spending most of its time with gossip and meaningless content.

On the other side, a generation that lived through the world’s biggest crises, witnessed peace and progress, was happy with what they had — yet at the same time consumed and enjoyed development as if resources were infinite.

Now that things are no longer going as they’re used to, they spread irrational fears.

Alongside all this, technology is advancing, giant tech companies are growing, and power-obsessed maniacs are trying to influence the masses. And all of them hide behind one word: freedom of expression.

We misunderstood freedom of expression so badly that everyone now talks about it. Knowledge has lost all importance. Mutual respect and understanding have lost all importance.

Once algorithms amplify this dynamic, freedom of expression turns into: “I hear only what I want to hear. I say whatever nonsense I want, and no one can interfere.” In this way, freedom of expression really only means monologue. Because contrary to what it claims to be, no opposing view is accepted; it’s seen as an attack on one’s own freedom of expression.

For example, hurling insults at minorities defending their rights is considered freedom of expression — but those minorities raising their voices in the streets to defend themselves is not. Spreading misinformation on social media is considered freedom of expression — but measures against it are not.

To express something means to communicate an idea or thought. Which means first, you need an idea or a thought. And for that, you need knowledge and evaluation.

Unfortunately, these have lost all meaning. The only “true” knowledge now is what is most consumed on the internet. If you confirm what people already want to hear, then it becomes “truth.”

Or, even more dangerously, words spoken firsthand by an individual are accepted as knowledge. This is exactly what populist politicians exploit: it’s enough for them to say “it happened this way.”

Or, as we’ve seen many times, someone makes an accusation. Before the court case even begins, the accused is declared guilty and lynched. Because knowledge no longer matters.

Another problem is our understanding of democracy.

In Turkey this is an even bigger issue, because between 50.1% and 100% there is no difference. A 0.01% difference counts as absolute majority. And there are no democratic mechanisms to stop, to check, or to limit what is done with that power.

On top of that, there is no real participation in democracy. People think democracy means only voting. Individuals are rarely involved in the political process. They don’t influence local decisions, nor do they have the desire to.

For example, when a decision is made to destroy forests and farmland in a village to build a facility, the people living there have no say.

Once, I asked a relative: what do you base your vote on? How do you say this side is good and that side is bad?

As usual, they blamed the side they didn’t vote for, while knowing nothing of the program of the side they supported. When I asked how the problems they described would be solved, they had no idea.

The things they accused one side of not doing were in fact being done by that same side. Or the campaign promises they praised as achievements of their own side had originally been proposed by the other side.

So elections are really a blind process. We’re choosing the best liar. It’s like asking an illiterate person to pick a book. Like asking a random passerby to choose the microprocessor for a newly manufactured car.

If that’s the case, why have an age limit of 18? Babies should be allowed to vote too. Even pets, who now practically live like citizens.

Democracy is not being represented. Democracy is not representing others either. It’s not simply the right to vote and be elected.

Those with money can exercise the right to be elected. Those without money who exercise that right become the slaves of those with money.

Which is precisely why those with money want to be elected: for better networks, more power, and immunity from bureaucratic hurdles.

If there were a rule that the elected person and their close family could not run any business during their term, that their companies must be managed by trustees, and that they would only receive a salary — then today, the same parliament that complains “600 members is too many, let’s cut it to 100” would be the first to object.

Does anyone really feel represented?

I don’t feel represented in either Germany or Turkey.

In Turkey, even if I disagree with most of the options, or if only 10% of one side aligns with my thoughts, I’m forced to support that alternative — because all other votes are meaningless. That’s why I initially thought election alliances were somewhat positive.

But eventually, elections turned into a battle between a conservative right-wing government and its equally conservative but slightly modernist opponents. So we’re not choosing apples and oranges, we’re just choosing apples.

In Germany, I don’t yet have voting rights, but things work a little more transparently and logically. Besides the federal parliament, there are state parliaments. Alliances are usually based on democratic values, not on “anything goes.”

Even if there are back-room deals, people here seem to have more influence over local decisions. This setup helps prevent past tragedies from repeating. For bureaucracy, it may have downsides, but socially, the checks built into the system are mostly positive.

Otherwise, dozens of people wouldn’t be racing to migrate to Germany.

The U.S. system is similar, with its own dynamics and checks. States are generally strong. There are still absurdities in terms of majority rule, but no one has the luxury of changing the constitution on a whim.

Judicial independence and power are exemplary. Today, the biggest threat is the orange man obsessed with inflicting maximum damage on the system.

I don’t know where the world is heading. The more I see people and the debates they engage in, the more my hope diminishes.

The only thing I know is that the world’s most important problems never get as much attention as meaningless power struggles.

During the recent floods in Spain, people were saying the floods happened because of the government. This is not a joke. What can you even say to people like that?

Sadly, these people make up the majority in many places — and thanks to social media, they reinforce their arguments by saying: look, people everywhere think like us.

Wars, hunger, climate-change disasters, the destruction caused by our consumption habits, the resurgence of old diseases, resource crises — none of this interests anyone.

What draws attention instead are things like deporting migrants who fled because of those very issues, or turning diseases into conspiracy fodder, or brushing off disasters.

People get more worked up over criticizing alternatives to resource problems — “they don’t want us to eat meat!” — than the problems themselves.

They get more excited about building walls, about fairy tales against vaccines, about those same walls again.

I think democracy and freedoms were too much for humankind to handle. Technology, which was supposed to advance humanity, has dragged us backward. Liberalism has been misunderstood.

As humans drifted away from nature, they forgot what nature meant and became victims of their own greed. When people got used to endless streams of content, they lost empathy.

They forgot how to be human. They remember it only when it directly affects them.

Take Gaza, for example. Someone living far away cannot truly empathize. People may say it’s terrible, they may feel sad, they may try to do something — but they cannot feel it in the same way.

In Turkey, it resonates much more deeply. The war in Ukraine is similar for Europe. Turks cannot empathize as much, but Europeans feel it closely.

The same goes for China’s social experiments, Taiwan, wars in Africa, wildfires in Australia, earthquakes, conflicts in South America — each resonates differently depending on closeness.

Thousands of years ago, democracy suffered the same illnesses. Hundreds of years ago, science faced the same struggles. The only difference now is the tools we use.

I hope this wave of 20th-century politics passes quickly. That we move on from politicians who lived through that century, from people defending their views, from the majority that has turned its back on science.

I hope we truly open our minds and begin to talk about real issues.

I don’t think there will be a new world war, but wars and disasters will likely always be right next to us.

Leave a comment