A Brief Essay on Absurdity and Mediocrity

What I mean by absurdity are things like political decisions, people attacking or killing one another, constant arguments, threats, statements, mistakes, and failures — all of it.

Sometimes, after reading a piece of news, we find ourselves saying, “No way, this can’t be real.” Other times, “How can someone be this stupid?” And in the end, we surrender to the thought, “They must know something we don’t” — especially when those we consider smart contradict themselves or the values we once believed they stood for.

I believe this is partially a problem of democracy. I don’t remember who said it, but when asked why democracy, someone replied, “Because it’s the least bad among bad systems.” Despite being debated for thousands of years and still facing fundamental issues today, it remains — at least relatively — the most fair system we have.

To be honest, I don’t think we’re that different from monkeys — especially when it comes to decision-making or social behavior. That may sound arrogant, but I include myself in this primitive behavior too. I’ve accepted it.

Still, let’s look at some data — if nothing else, to have an excuse for this discussion.

The Numbers

- In Turkey, the proportion of university graduates is 41.4% among those aged 25–34, and 10.8% among those aged 55–64.

- Only about 0.3% of the population completes a PhD.

- The most studied subject in Turkey is Business, while Education ranks lowest. Medicine and Engineering sit somewhere in between.

- Apart from Business, Turkey is below the global average in all major fields.

- The proportion of international students in Turkey is also quite low.

- Globally, only 6.7% of the population holds a university degree. Master’s degree holders are around 1%. Those with a background in Social Sciences: 2.5%. PhD and above: 0.5–1%.

- Global literacy is about 86%, while Turkey’s is 97%.

- 66% of all books published worldwide are sold in the U.S., China, Germany, Japan, and India. (Germany has a population comparable to Turkey.)

- Only 30% of the global population read a book in the last month — any book at all.

- In Turkey, 68% of the population does not read books. The average time spent on reading is 1 minute per day. In the U.S., it’s 6 minutes; in Europe, around 1 hour.

- Those who govern us — politicians, business leaders, bureaucrats — make up about 0.5–1% of the population.

- 35% of the world’s wealth is held by 1% of the population.

- 85% of all wealth is controlled by 10% of the people.

So where am I going with all of this? Honestly, I’m not sure either. It’s difficult to draw meaningful conclusions from a mix of incomplete, approximate, or loosely related data. But still, even this loose collection of numbers gives us a sense of how absurd the system is.

At best, 80–90% of the population contributes neither intellectually nor economically to the world or to their own countries. They have no real ideas or opinions — they exist merely as part of the labor force. And due to democracy, this majority elects their leaders.

As for those who govern — the people who manage capital or hold power — most of them are not particularly thoughtful or deep individuals. Globally, the number of people who truly think about the system, study it, engage with its philosophy, sociology, or science is a tiny minority — and their influence is likely limited, if not completely absent.

As a result, the voters, who make up the majority, are guided by the most primitive instincts, and the elected are often those who are best at manipulation — whether through money, power, or populism. These individuals become the model for what a “leader” should be.

These mediocre figures go on to make appointments, pass laws, sign off decisions, and propose new ideas. It’s hard to believe that many of their decisions have any real foundation. In other words, we are drifting toward a deeper systemic incompetence. And within this sea of mediocrity, the number of people who genuinely understand social issues, can empathize, think critically, or offer solutions — is probably countable on one hand. On both the voter and leader sides.

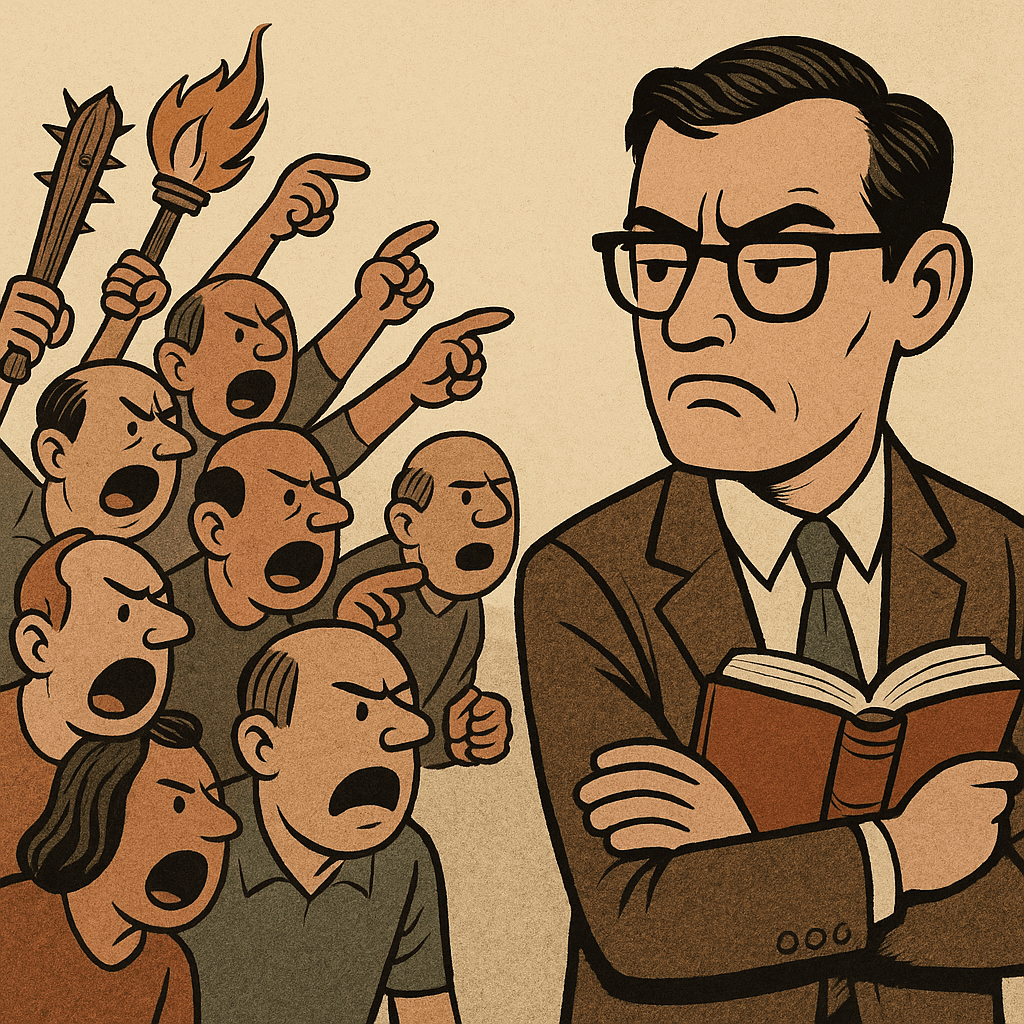

And so, while we reflect on certain topics and feel “enlightened,” we make the mistake of thinking everyone else must be thinking the same way. Then we’re surprised by the absurdities we see. Or we label experts arrogant when they speak. But looking at the statistics, I’d argue the expert shouldn’t even bother trying to explain anything — because there’s no one capable of understanding it.

This also explains why social media, newspapers, and TV debates feel so hollow. They go nowhere. Everyone speaks from their own echo chamber. The audience, for the most part, has no real grasp of the issue.

The same goes for popular science. Experts in various fields try to explain and spread knowledge out of enthusiasm, love of science, or the need to engage with the public. But in the end, things go off the rails. Can they not? I don’t think science should even aim to reach the general public. Discussing science outside of scientific circles serves little to no purpose.

And when things do get debated, they devolve into an absurdity wrapped in the blanket of “freedom of speech.” On the internet, unfiltered information is often interpreted emotionally by people who gravitate toward pseudo-experts — people who just “sound” knowledgeable. Once they emotionally connect to a piece of content, they adopt it and even start selling it as truth. There’s nothing you can do about this — because any reaction you give is immediately branded as an attack on free thought.

“Who are you to say otherwise?”

Add to this the misinformation, AI-generated content, and media-fueled nonsense, and knowledge itself starts to lose meaning. No matter what you say, you’re up against a system and society that makes decisions based on emotional, irrational foundations, often led by non-experts.

Would a system based on rationality and truth be better? I doubt it. Because then we’d neglect emotional and individual aspects, which are just as important and would be left unaddressed.

That’s why the paradoxes of democracy remain… paradoxes. Its most essential requirement is access to quality knowledge — but that itself is a whole separate problem involving global inequality, accessibility, and information integrity.

In Short

Maybe it’s best to just mind our own business — or at least not take this pervasive mediocrity personally. Recognize the futility of most arguments, and avoid spending time on things beyond our sphere of influence. Neither the past was better than today, nor the future will be any brighter.

The world will keep spinning, generations will keep shifting, and human mediocrity will continue just the same.

So yes — in the end, I too ended up adding to the absurdity I set out to criticize.

Leave a comment