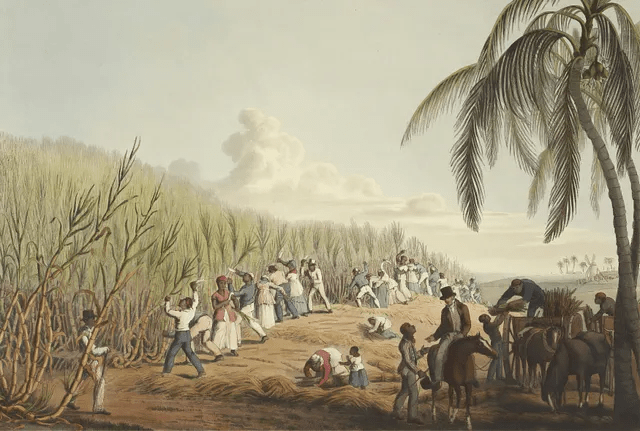

Free Slaves: The Paradox of Modern Work Life

I titled this piece Free Slaves because we, the white-collar workers, are just that — free slaves. Or worse, we’re the tribe members who betrayed their own to ensure the efficient functioning of the system, believing ourselves to be masters.

We call ourselves “free” because outside of work, we feel free. The one-month vacation we get, the material possessions we can afford — these trick us into believing we have liberty. But we design our entire lives around the necessity of work. Add a mortgage, car loan, and maybe a child to care for, and the concept of freedom slowly and silently self-destructs.

I’ve never liked the corporate slogan “we’re a family.” Why should we be a family? We are a group of unrelated people brought together by money. For engineers, things might be slightly different — they often do what they love. But since they’re doing it within a corporate system, they can’t fully do it their own way.

I also don’t agree with those who say, “There’s no such thing as a work friend.” Of course there is. There should be — as long as your “friend” remains professional. Without professionalism, things can get messy fast.

So where do I draw the line? Only on two things:

- Professionalism, and

- Creating a healthy work environment.

Professionalism prevents us from taking things personally. Everyone understands their role and separates work from private life. If you argue with a close colleague, it ends after work — or it ends once work begins.

The second point is just as vital. We spend a huge chunk of our lives at work — sometimes more time than with spouses, friends, or even our own children. So it’s crucial that we feel at ease with the people we share this time with — or at least feel some sense of harmony.

Because I work in a small company, I have a lot of direct interaction with my team. In larger companies, things may be more distant. But what I’m about to say applies universally: even if you’re not part of the core team, you need to ensure the team you’re building is made of people who trust, support, and align with one another. That’s the most crucial factor in any project’s success.

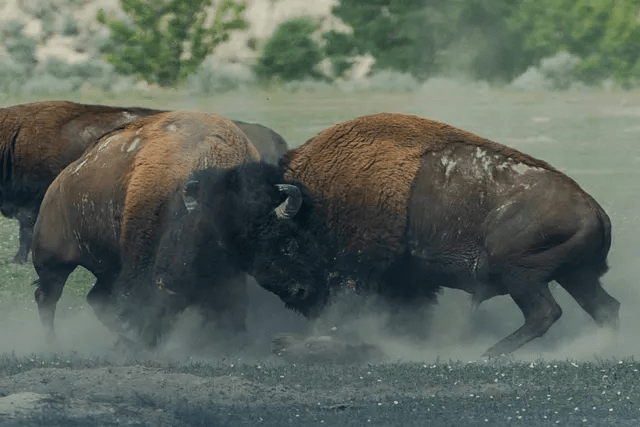

Otherwise, you end up like those teams full of stars but incapable of achieving anything.

When it comes to hiring for a project, the first step is knowing what you’re looking for: what strengths you already have and what’s missing. Based on that, you can do interviews, skill tests, and technical evaluations.

Also, consider how critical the roles are. Can you tolerate delays from training and adaptation? Is this a short-term project or a long-term vision? If it’s long-term, motivation might matter more than raw technical skill.

Sometimes, a candidate who doesn’t exactly match the job description ends up being far more valuable — bringing an outside perspective that reveals blind spots you never even knew existed. That’s why I believe motivation and versatility should never be underestimated when building a strong team.

But it doesn’t end with hiring. You must also understand the new hire’s expectations and desires, and get them up to speed quickly. Smaller companies often skip this step, lacking a structured onboarding process, which can lead to negative outcomes.

Even without a formal training system, at least assign a reliable mentor for the first year. This accelerates knowledge transfer and keeps morale high.

From the employee’s side: if the onboarding process is unclear, two things matter:

- Clear communication – Just as the company is making a choice, so are you. During the trial period, it’s essential to express your expectations and needs clearly.

- Regular feedback – Working with Germans taught me the value of structured feedback. Germans are highly individualistic. If you ask for help, they’ll give it wholeheartedly. If not, they’ll smile and stay out of it, even if things go wrong — and one day, you’ll just be let go without warning. So feedback is vital.

In Turkey, it was the opposite. There was constant monitoring, advice, and evaluation — but never formal. All those hallway chats led to zero real insight. That’s why you should demand formal feedback, wherever you are.

I usually ask for weekly feedback during the first month, biweekly after that, and monthly after the third month. Annual performance reviews come later. It doesn’t always have to be formal meetings — even kitchen or smoke-break talks can do, as long as they’re honest and direct.

Now let’s talk about conflict.

A project is like crossing an ocean through storms — encountering problems is part of the journey. Conflict often arises from poor communication: misunderstanding, taking things personally, lack of leadership, or not listening. Add corporate politics and rigid formalities into the mix, and things spiral.

I personally dislike formality. I find it unnecessary. I believe everyone in a company should be able to joke around and tease each other. But when it’s time to work, everyone should know their role and do it without emotional baggage.

Of course, not everyone likes a casual atmosphere. Some people find joking invasive. We should respect that too.

When things are going well, personal tensions stay buried. But when things go wrong, everyone shows their true face — some go on defense (usually hiding a mistake), others attack, and some simply don’t care.

In such moments, the calm, rational person wins. But winning shouldn’t be the goal. If this is a ship, you either sink together or survive together.

The key during conflict is to quickly accept the problem and seek solutions — not blame. Don’t obsess over fairness. At that moment, forget everything that came before and focus on fixing the issue. Justice comes after the project ends.

While you’re solution-focused, there will be resistance — loud voices, silent types, and complainers. But the stronger the team harmony, the quieter these voices become. Because good teams know each other’s strengths and weaknesses — and adapt accordingly.

This is what I mean when I say I dislike formality. In a less formal but still professional environment, it’s easier to be honest. Everyone knows they’ll face each other again tomorrow, and probably laugh again. So instead of blowing up small conflicts, people just deal with them.

A solid team isn’t just the key to success — it’s also the key to peace. And peace fuels motivation. Motivation leads to better, higher-quality work.

Why does all of this matter? I’m not entirely sure.

But if we must be slaves, then at least let us be good ones — in this brief life we’re given.

Leave a comment